The Myth About Corridors

Originally from behance.net

Look at any plan of a building today and you will almost always find one architectural element: the corridor. The separation of buildings into specific functioning sets where the corridor assumes the role of circulation has become so commonplace that it can be considered a principle, a principle that has neither been developed further nor put to question. The function of the corridor as only circulation space is a myth. In fact, the corridor is actually a relatively modern device that first appeared in English aristocratic homes in the 17th century to separate the noble household from the servants.

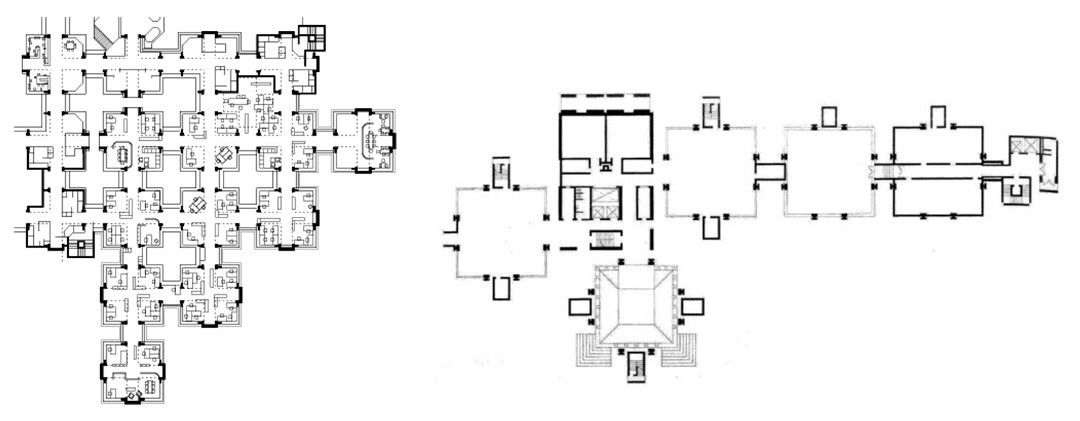

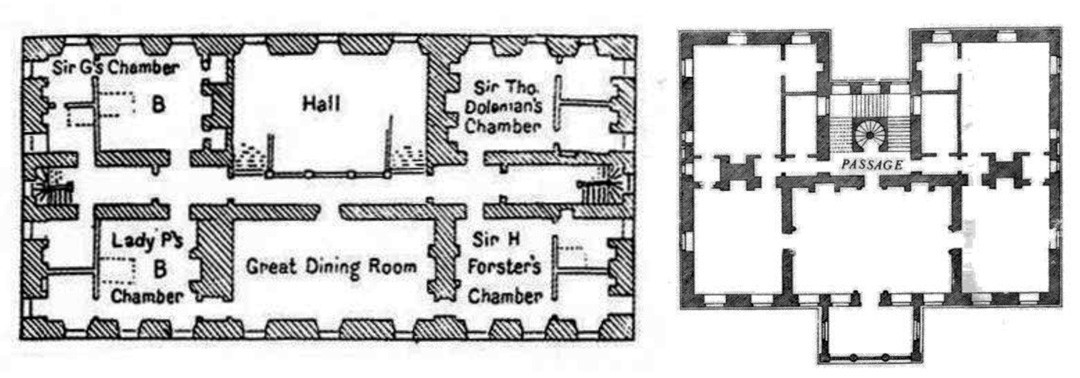

As Robin Evan writes in his essay Figures, Doors and Passages, the corridor was intended primarily to split those who served and those to be served so that a direct sequential access for the privileged family circle could be maintained while servants were consigned to a limited territory always adjacent to, but never within the house proper. It is important to note that in the Evans‟ examples of Coleshill, Berkshire by Sir Robert Pratt (1650) and Amesbury House by John Webb (1661), even though the corridors and back servant stairs collectively form a network of spaces that touch every major room in the household, enfilades remain the primary means of movement through spaces of inhabitation by the ladies and gentlemen of the house. The arrangement of rooms in its hierarchy and function was also still very much governed by this sequence of movement from one room to the next, and not by the corridor. The house proper retains the formal composition from the Italian Renaissance as extolled by Italian theorists Alberti and Serlio, while the corridor was simply a device to restrict the interaction of lower ranks of society within the domain of the noble household, at a time of rising antagonism between the rich and poor in society.

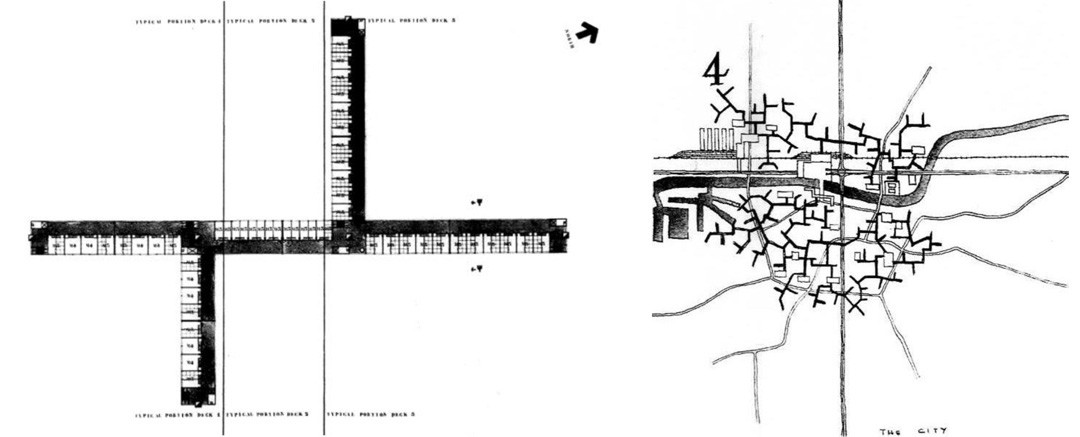

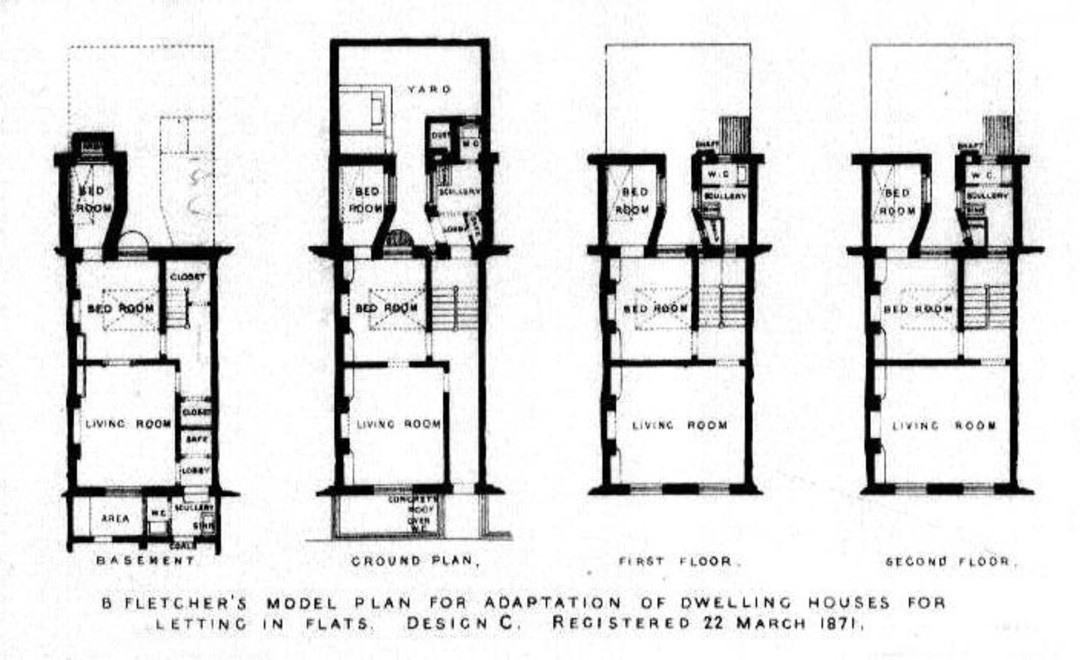

The perception of the corridor undergoes another crucial change in the early 20th century. In a Fordist world where surplus value is derived primarily from the mass production of cheap commodities, efficiency was of paramount importance. The dictum of „the greater the turn over, the higher the profits‟ led to assembly lines in factories where each worker concentrated on a specific part of the production process to achieve maximum productivity with minimal redundancy. Efficiency however, was not limited to the relationship between the worker and the product. The pursuit of efficiency extended beyond the workplace as a philosophy such that an ideal way of life encompassed the efficient production, distribution and consumption of goods. In this context, the corridor gains an economic dimension and was seen as a highly valuable asset that supported the consumerist lifestyle of the early 20th century by allowing the uninterrupted movement of people and goods from one space to another. The corridor as circulation divided a space into two clear parts – its inhabited rooms and unoccupied circulation space, which gave each space a clear purpose without any overlap of function or unused excess. It was no longer necessary to pass serially through rooms and be encumbered with needless encounters. Instead, the door to any room opened into the corridor from which the room next door and the ones at the extremities became equally easy to access. The thoroughfare drew the extremities closer, and facilitated deliberate communication. At the same time it reduced accidental contact which was regarded as distracting, corrupting and malignant in an era where adding value to commodities was the key means of production, not interaction. The corridor becomes valued for its ability to connect, which gives rise to our contemporary understanding of corridors as circulation spaces.

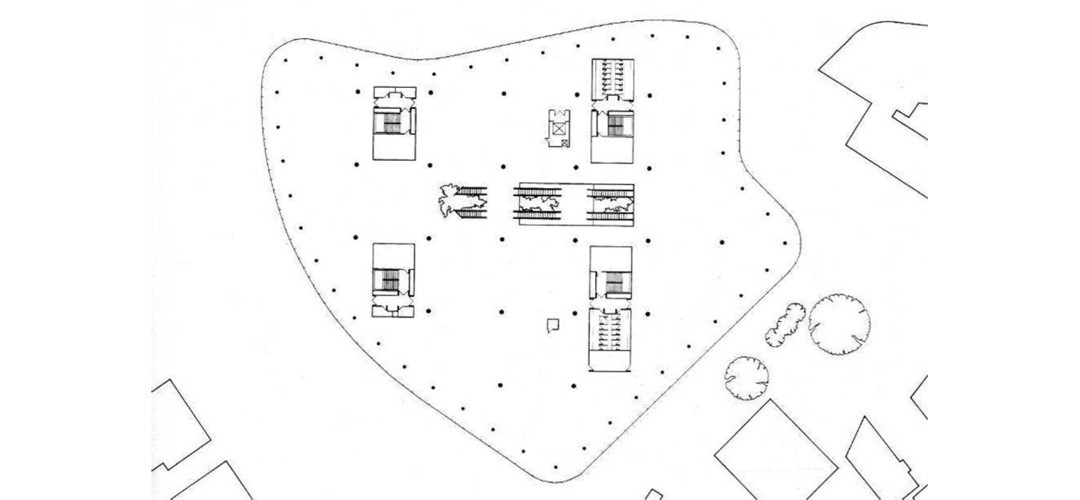

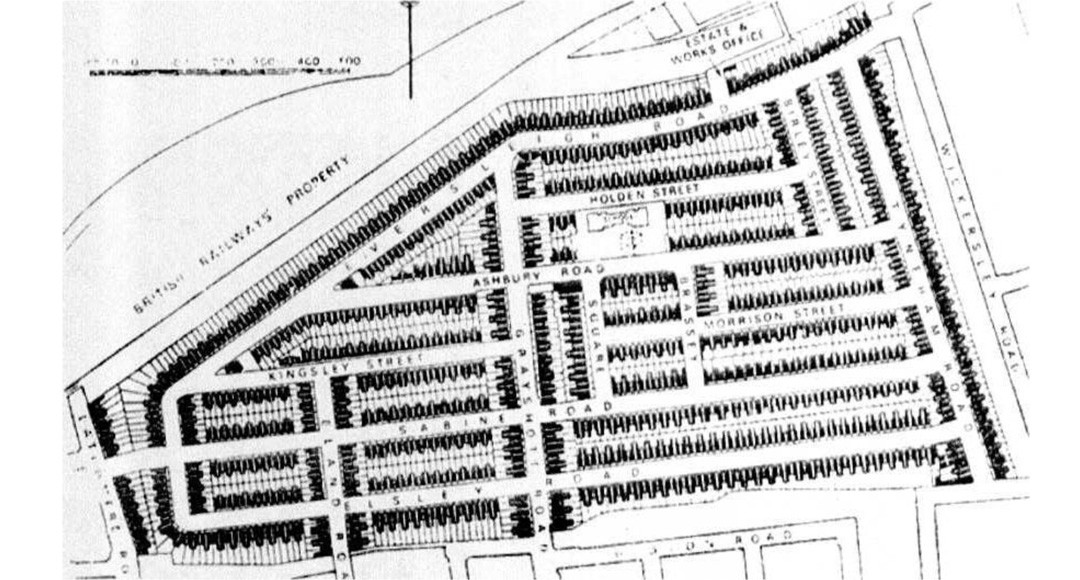

Thus it can be seen that the notion of a corridor as circulation is a very modern concept that is intrinsically linked to a Fordist model of economy. The corridor as an organisational element in itself has evolved in its function over the years, first as a way of separating social classes, then as part of a political solution for segregation of the working population, and finally to an economic asset as an effective means of circulation in the early 20th century. Though it is true that the observations listed above show the corridor being used as a space for movement tovarious degrees, it was only in the early 20th century that the corridor truly achieves its functional raison d'être and becomes deliberately "streamlined" with all clutter and facilities removed for the sole purpose of circulation, as with other architectural elements such as stairs and ramps that have become equally synonymous with circulation during this period. In this sense, to see corridors as spaces of circulation would only be a valid assumption to make in a Fordist world. But when it is considered in relation to the larger context of the house/office, then perhaps the corridor can only be defined abstractly and neutrally as a space that facilitates by separating or separates by facilitating depending on which attribute is valued. Louis Kahn famously termed corridors as "servant" spaces, recognising this unique reciprocal relationship between the corridor and room, adding to this a fixed hierarchy whereby the corridor is always serving and being subjugated by the space of the room.