Advaitic Epistemology

Pramanas#

Advaita Vedanta distinguishes six pramanas, means of valid knowledge. A pramana is that which produces knowledge that is in accord with reality, by which the subject knows an object.

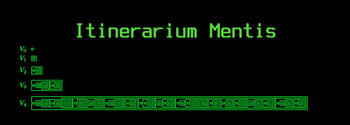

Following the Bhatta school of Mimamsa, Advaita Vedanta identifies six pramanas:

- pratyaksa (perception)

- upamana (comparison)

- anupalabdhi (non-cognition)

- anumana (inference)

- arthapatti (postulation)

- sabda (testimony)

Hierarchy of Knowledge#

Two kinds of knowledge (vidya) to be attained, the higher (para) and the lower (apara).

- Para vidya, the higher knowledge, knowledge of the Absolute. Reality.

- apara vidya, the lower knowledge, knowledge of the world (objects, events, means, ends, virtues, vices). Phenomenal world.

The two kinds of knowledge are incommensurable since the higher knowledge is sui generis and is reached not through a progressive movement through the lower orders of knowledge but all at once, as it were, intuitively, immediately. Higher knowledge is self-certifying, no other form of lower knowledge, such as inference or perception, is capable either of demonstrating or of refuting it.

From the viewpoint of para vidya all other forms of knowing or modes of knowledge are equally apara vidya. But until that spiritual wisdom, the vision of non-duality, is attained, the lower knowledge as knowledge holds good. Any attempt to demonstrate the falsity of all knowledge without reference to an eternal Absolute is doomed to failure for the mind that would deny its own logic without reference to Brahman must be committed in advance to the use of that logic and any denial would thus be self-contradictory.

The final goal of knowledge, spiritual intuitive insight, once attained, relegates all other forms and types of knowledge to a lower knowledge. The pramanas, such as perception, inference, and comparison, are justified as valid means of knowledge as long as they do not have any pretensions to finality or ultimacy.

Once Brahman is known, all else is known, but this does not mean that a knowledge of Brahman carries along with it a knowledge of particulars, of individual objects and their relations in past, present, or future time, for Brahman is incommenurable with the empirical world. The empirical world of multiplicity, disappears from consciousness upon the attainment of the “oneness” that is Brahman. Paravidya is thus not some form of supernatural, magical knowledge about Nature. When Brahman is realized, nothing else needs to be known.

The ontological source of avidya#

The question like the ultimate “why” of avidya cannot be intelligibly asked, since knowledge destroys ignorance and there is no ignorance whose origin stands in question from the standpoint of knowledge. When in ignorance one cannot establish a temporal origin to what is conceivable only in time or describe the process by which this ignorance ontologically comes to be.

Note: this is much similar to omniscience, or of how God's language is not temporal. And paradoxically it seems that this kinds of arguments “limits” the “power” of omniscience, or of Absolute. No attempt to reconcile the Absolute and the finite is made in advaita vedanta.

Self-Validity of all knowledge#

Svatahpramanyavada, the theory of the self-validity of all knowledge. For the Advaitin, first of all all knowledge is intrinsically valid, in that validity arises from the very conditions that make for knowledge in the first place. But only that knowledge or experience is ultimately valid which is not contradicted by any other knowledge or experience. An idea is held to be true or valid the moment it is entertained, and it retains its validity until it is contradicted in experience or is shown to be based on defective apprehension.

Svatahpramanyavada is a kind of pragmatism, instead of truth happening to an idea, it is falsity that happens. A cognition is like the accused in court who is considered innocent until proven guilty; it is considered true until it is shown in experience to be false.

Thus svatahpramanyavada is a psychology of belief, and it involves a logical justification of the way in which we believe.

This whole process is belief is justified, for there is no place outside of the knowledge acquiring process itself where we may look for a way to confirm a judgement. In particular, cognitions must be taken as self-luminous, since if it were necessary to make a supporting inference to sustain the validity of one's cognition, then one would be placed in the position of having to make an infinite number of such inferences, for each supporting inference would require another one, ad infinitum.

The Naiyayikas, who are the chief opponents of the Vedantins in this respect, hold that truth consists of a correspondence between statement and reality, with the test of truth being a valid inference supported by “fruitful activity”. The Vedantin would argue as follows: A judgmenet is not validated by an inference and a supporting experience because the premises of the inference would have to be establisehd by some other inference and the supporting experience would have to be shown to be conclusive, and so on indefinitely. We look for support for a judgment only when we are in doubt about it, and we are able to eliminate this doubt only when we are unable to find the kind of conditions that act in such a manner to falsify the judgment. There need to be no test for truth because non-contradiction is the sole guarantee of validity.

Non-contradiction here does not so much mean an absence of logical self-contradiction, as it means the impossibility of subration. This applies ultimately only to Reality, hence it while insuring the validity of the pramanas also leads to their ultimate non-validity.

- About the possibility of doubt:"One can have a doubting cognition, but one cannot meaningfully be in doubt about one's cognition".

- -One can never be sure of truth in any positive sense of the term, all that one can know is that they ahve not been shown to be false. This is compatible and necessary to the metaphysical position of Advaita Vedanta.

The proactive character of perception, and as an act of involvement#

Perception is that means of knowledge that is obtained through an immediate contact with external objects. Perception, according to Advaita Vedanta, takes place when the min, through the various senses, assimilates the form of the object presented to, or selected by, it and appropriates it to itself. Perception requires a modification of the mind in its proper form after the form of the object; it requires an illumination of the object by the light of consciousness.

The mind for Advaita does not simply receive stimuli or impressions passively, combine them into percepts, and manipulate them whiel retaining in an unaltered form, its own structures. THe mind is active from the start in its relation with the objects and takes upon itself something of the character of the object. For Advaita, to know an object perceptually means to become that object and to have it become a part of one.

Consequently, the self, in that state of consciousness wherein perceptual experience takes place, is always involved with the world. To be awake means to be caught-up with forms and relations. Perceptual experience notonly illuminates an outer world to consciousness but also brings the changing world into consciousness; it involves the self in the world.

Reason#

The manner one takes the power and limits of reason influences fundamentally the manner in which one interprets the world.

The theory of inference in Indian philosophy generally differs from classical Western logic, especially in that it involves a kind of scientific method of induction as part and parcel of it and hence is never purely formal in character. E.g. the null class is not admitted in Indian logic; all terms of an argument must have memebers.

Inference (anumana), for Advaita, is thus an empirical pramana, of which the task is to draw out the implication of sense-experience. In doing this the inference is necessarily limited or relative in that every vyapti or invariable relation between what is inferred and the cause from which the inference is made has a probabilitstic factor attached to it.

The universal proposition is accepted as true as long as no single crucial experiment or obvservation falsifies it. There is always the possibility that a future observation will falsify it. No rational necessity is attached to any universal proposition or scientific hypothesis.

The basic guiding principles that inform this pramana such as causality bear no rational necessity. They are essentially heuristic. Accepted in order to enable us to organize perceptual facts, to predict sequence of evenets, and to guide us in our search for new facts and relations.

Hence in its epistemology, Advaita Vedanta's main concern is to describe the primary moments of spiritual experience and to lead the mind to it. Reason is of value in enabling one to function in the world; and it is of greatest value when it enables one to transcend oneself and acquire therey immediate understanding.

Realistic epistemology#

Advaita Vedanta rejects the position that the object of experience can be reduced ontologically to the knowing/perceiving subject, and insists upon the separation of the subject and the object within the phenomenal world. This rejection of subjective idealism becomes the affirmation of a special kind of realistic epistemology.