IV

Within Scholasticism itself this principle resulted not only in the explicit unfolding of what, though necessary, might have been allowed to remain implicit, but also, occasionally, in the introduction of what was not necessary at all, or in the neglect of a natural order of presentation in favor of an artificial symmetry. In the very Prologue of the Summa Theologiae, Thomas Aquinas complains, with an eye on his forerunners, of “the multiplication of useless questions, articles, and arguments” and of a tendency to present the subject “not according to the order of the discipline itself but rather according to the requirements of literary exposition.” However, the passion for “clarification” imparted itself —quite naturally in view of the educational monopoly of Scholasticism—to virtually every mind engaged in cultural pursuits; it grew into a “mental habit.”

Whether we read a treatise on medicine, a handbook of classical mythology such as Ridewall’s Fulgentius Metaforalis, a political propaganda sheet, the eulogy of a ruler, or a biography of Ovid, Note 24 we always find the same obsession with systematic division and subdivision, methodical demonstration, terminology, parallelismus membrorum, and rhyme. Dante’s Divina Commedia is Scholastic, not only in much of its content but also in its deliberately Trinitarian form. Note 25 In the Vita Nuova the poet himself goes out of his way to analyze the tenor of each sonnet and canzone by “parts” and “parts of parts” in perfectly Scholastic fashion, whereas Petrarch, half a century later, was to conceive of the structure of his songs in terms of euphony rather than logic. “I thought of changing the order of the four stanzas so that the first quatrain and the first terzina would have come second and vice versa,” he remarks of one sonnet, “but I gave it up because then the fuller sound would have been in the middle and the hollower at the beginning and the end.” Note 26

What applies to prose and poetry applies no less emphatically to the arts. Modern Gestalt psychology, in contrast to the doctrine of the nineteenth century and very much in harmony with that of the thirteenth, “refuses to reserve the capacity of synthesis to the higher faculties of the human mind” and stresses “the formative powers of the sensory processes.” Perception itself is now credited—and I quote—with a kind of “intelligence” that “organizes the sensory material under the pattern of simple ‘good’ Gestalten” in an “effort of the organism to assimilate stimuli to its own organization”; Note 27 all of which is the modern way of expressing precisely what Thomas Aquinas meant when he wrote: “the senses delight in things duly proportioned as in something akin to them; for, the sense, too, is a kind of reason as is every cognitive power” (“sensus delectantur in rebus debite proportionatis sicut in sibi similibus; nam et sensus ratio quaedam est, et omnis virtus cognascitiva”). Note 28

Small wonder, then, that a mentality which deemed it necessary to make faith “clearer” by an appeal to reason and to make reason “clearer” by an appeal to imagination, also felt bound to make imagination “clearer” by an appeal to the senses. Indirectly, this preoccupation affected even philosophical and theological literature in that the intellectual articulation of the subject matter implies the acoustic articulation of speech by recurrent phrases, and the visual articulation of the written page by rubrics, numbers, and paragraphs. Directly, it affected all the arts. As music became articulated through an exact and systematic division of time (it was the Paris school of the thirteenth century that introduced the mensural notation still in use and still referred to, in England at least, by the original terms of “breve,” “semibreve,” “minim,” etc.), so did the visual arts become articulated through an exact and systematic division of space, resulting in a “clarification for clarification’s sake” of narrative contexts in the representational arts, and of functional contexts in architecture.

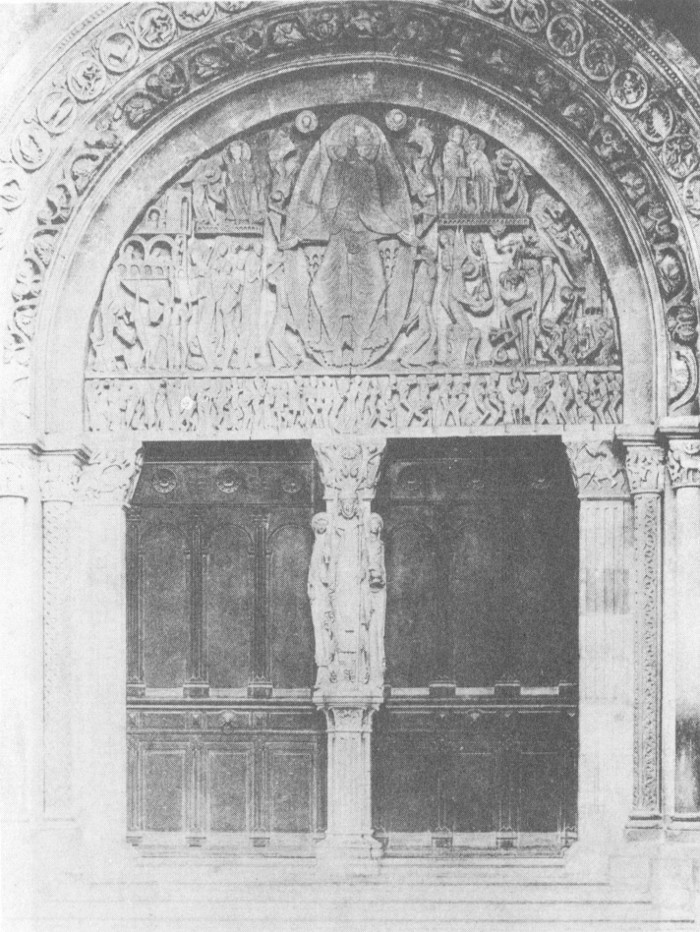

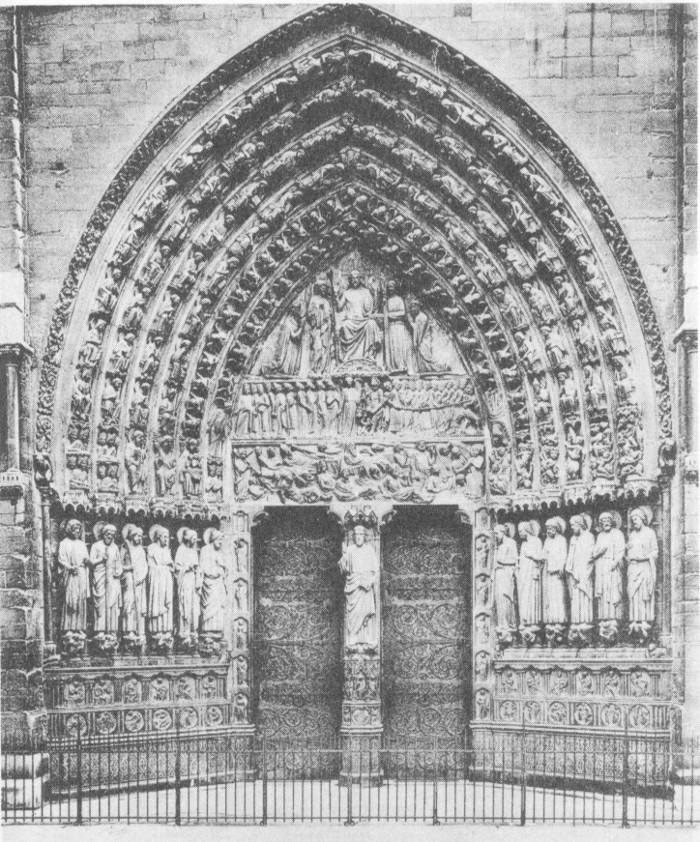

|  (much restored). Ca. 1215-1220. |

In the field of the representational arts this might be demonstrated by an analysis of almost any single figure; but it is still more evident in the arrangement of ensembles. Barring such accidents as happened at Magdeburg or Bamberg, the composition of a High Gothic portal, for example, tends to be subjected to a strict and fairly standardized scheme which, in imposing order upon the formal arrangement, simultaneously clarifies the narrative content. Suffice it to compare the beautiful but as yet not “clarified” Last Judgement portal of Autun (fig. 2) with those of Paris or Amiens (fig. 3) where—in spite of an even greater wealth of motifs—consummate clarity prevails. The tympanum is sharply divided into three registers (a device unknown in Romanesque save only such well-motivated exceptions as St.- Ursin-de-Bourges and Pompierre), the Deësis being separated from the Damned and the Elect, and these again from the Resurrected. The Apostles, precariously included in the tympanum at Autun, are placed in the embrasures where they surmount the twelve Virtues and their counterparts (developed from the customary heptad by a Scholastically correct subdivision of Justice) in such a manner that Fortitude corresponds to St. Peter, the “rock,” and Charity to St. Paul, the author of I Corinthians, 13; and the Wise and Foolish Virgins, antetypes of the Elect and the Damned, have been added in the doorposts by way of a marginal gloss.

|  |  |  |

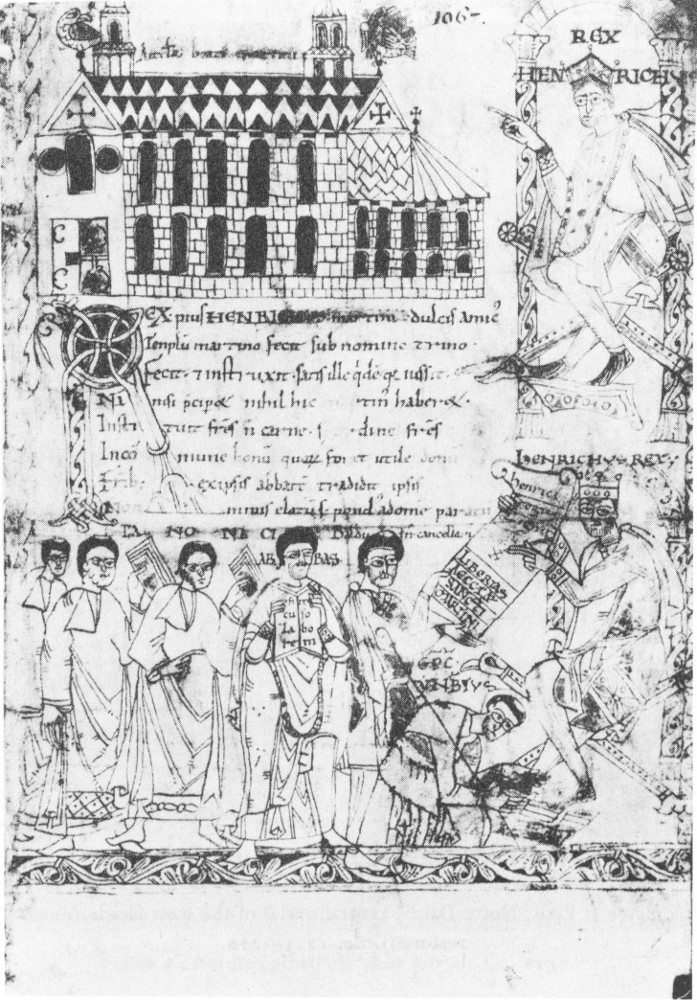

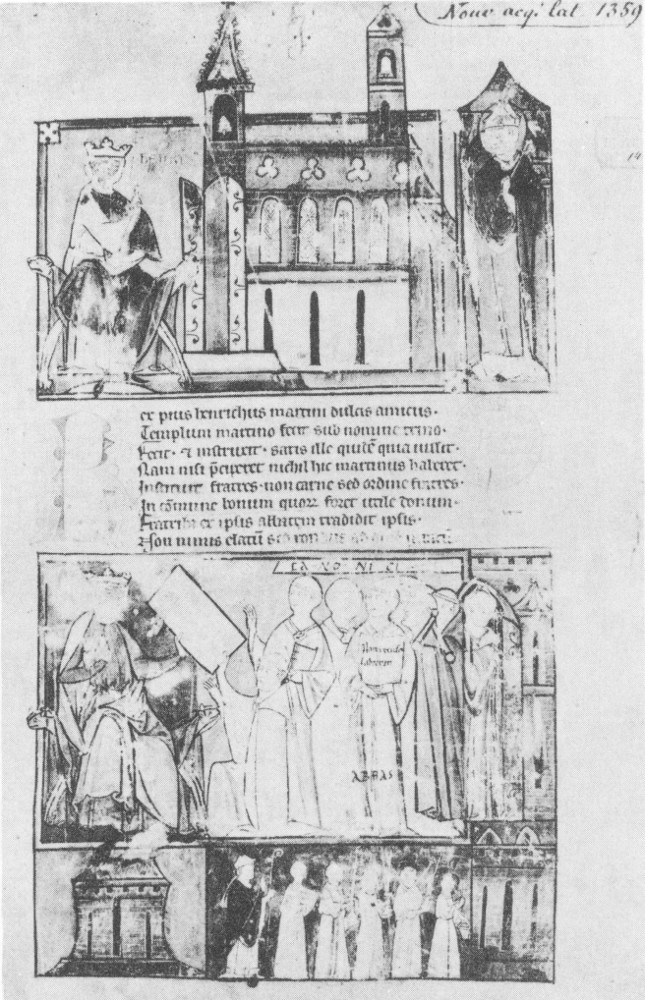

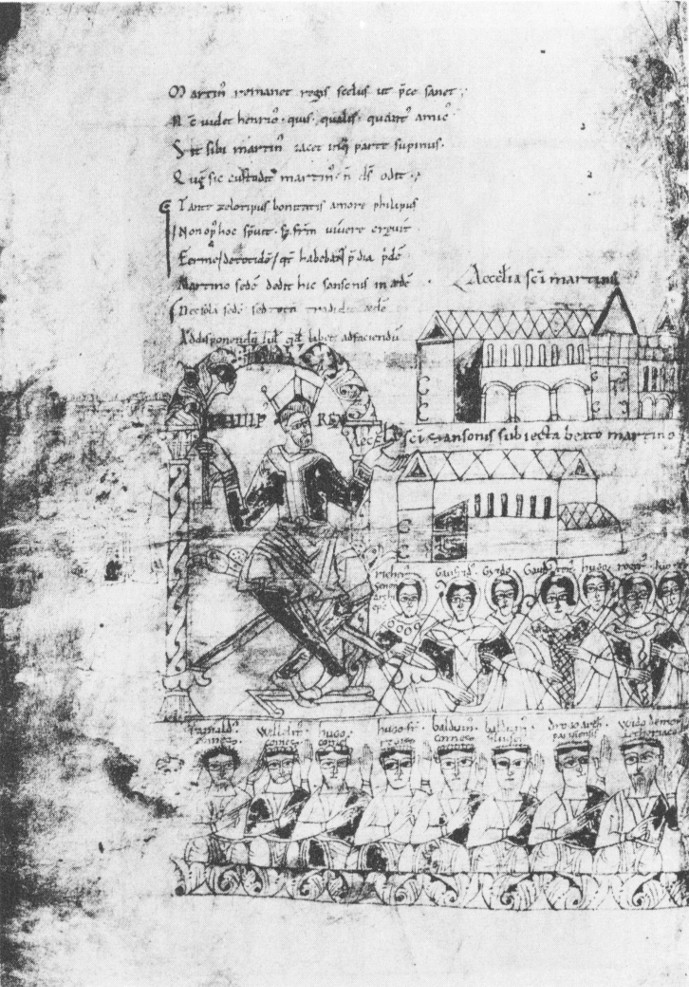

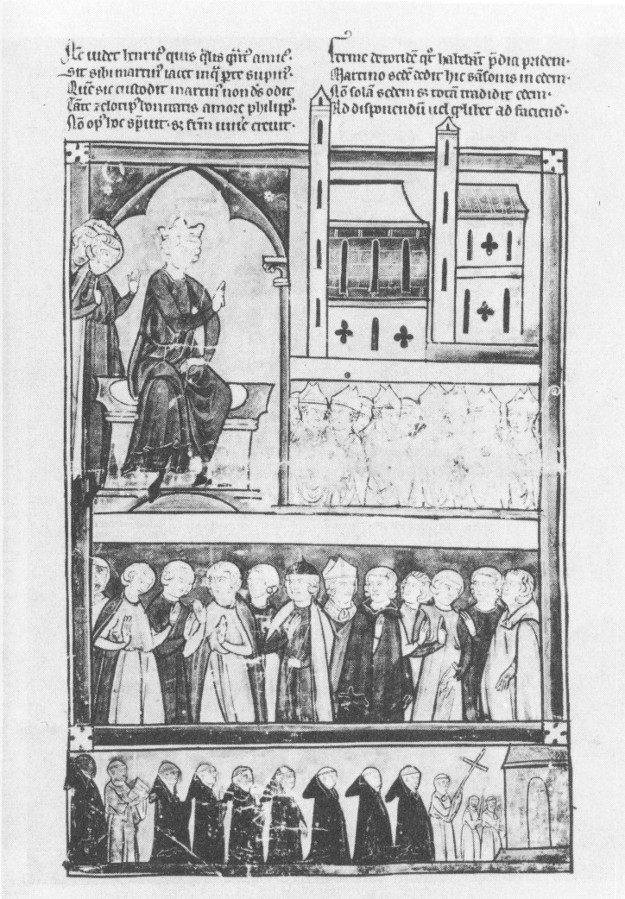

In painting, we can observe the process of clarification in vitro, so to speak. We can compare, by an extraordinary chance, a series of miniatures of about 1250 with their direct models, produced in the latter half of the eleventh century probably after 1079 and certainly before 1096 (fig. 4-7). Note 29 The two best known (fig. 6 and 7) represent King Philip I conferring privileges and donations, among them the church of St.-Samson, upon the Priory of St.-Martin-des-Champs. But where the Early Romanesque prototype, an unframed pen drawing, shows a jumble of figures, buildings, and inscriptions, the High Gothic copy is a carefully organized picture. It pulls the whole together by a frame (adding, in a new feeling for realism and communal dignity, a consecration ceremony at the bottom). Neatly segregating the different elements, it divides the area within the frame into four sharply delimited fields which correspond to the categories of the King, the Ecclesiastical Structures, the Episcopate, and the Secular Nobility. The two buildings—St.- Martin itself and St.-Samson—are not only brought up to the same level but also represented in pure side elevation instead of being shown in mixed projection. The fact that the dignitaries, formerly unattended and uniformly frontalized, are accompanied by some minor personages and have acquired the faculties of movement and intercommunication enhances rather than weakens their individual significance; and the only ecclesiastic who, for good reasons, has found his place among the counts and princes, Archdeacon Drogo of Paris, is clearly set off against them by his chasuble and mitre.

|  |  |  |

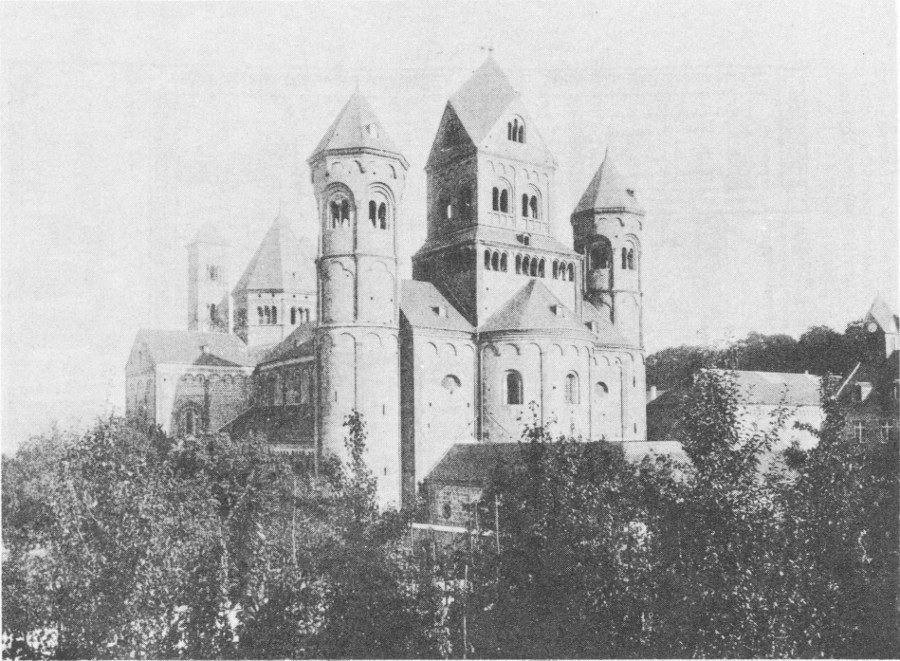

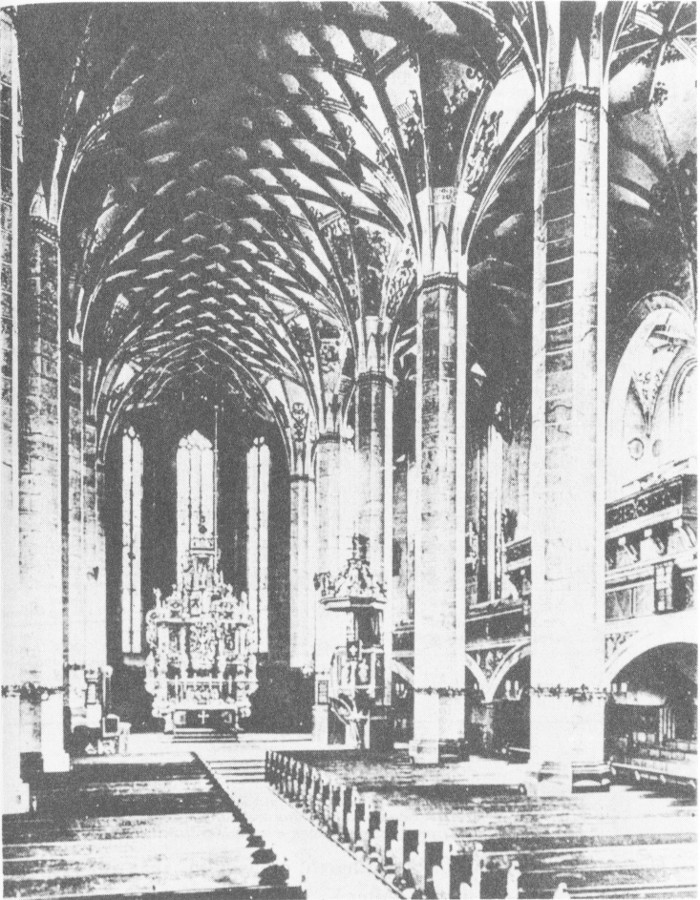

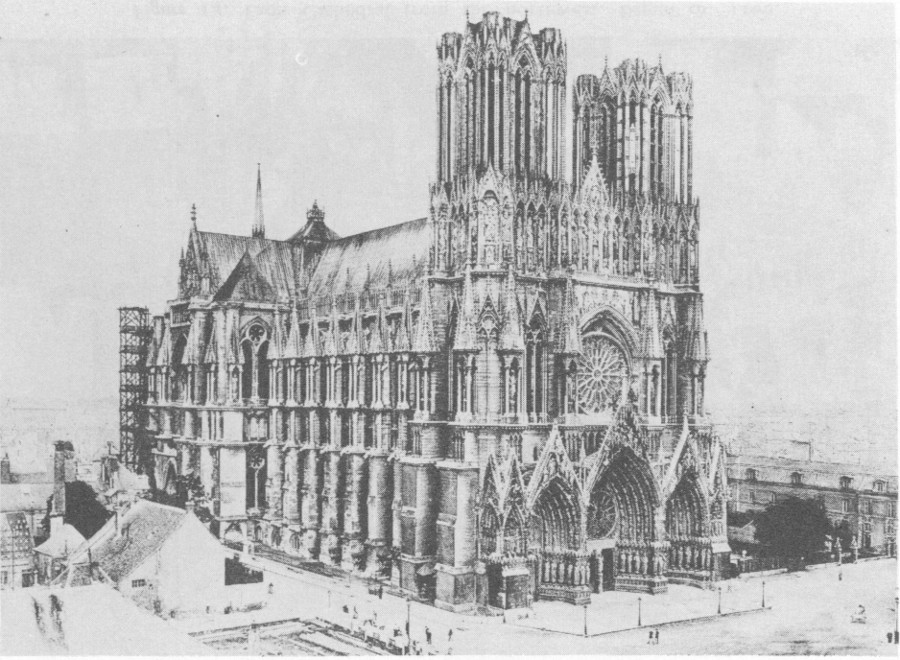

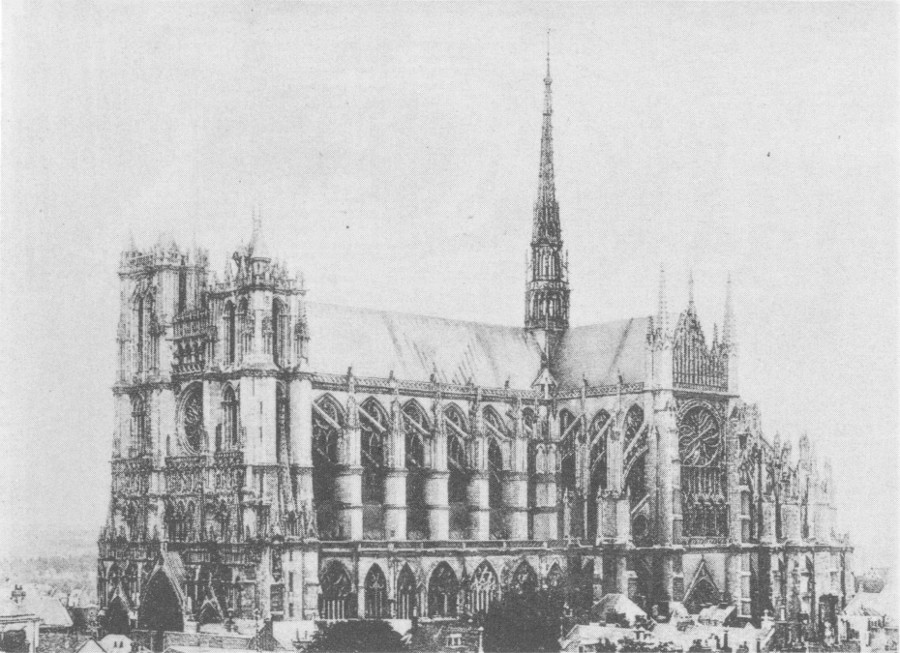

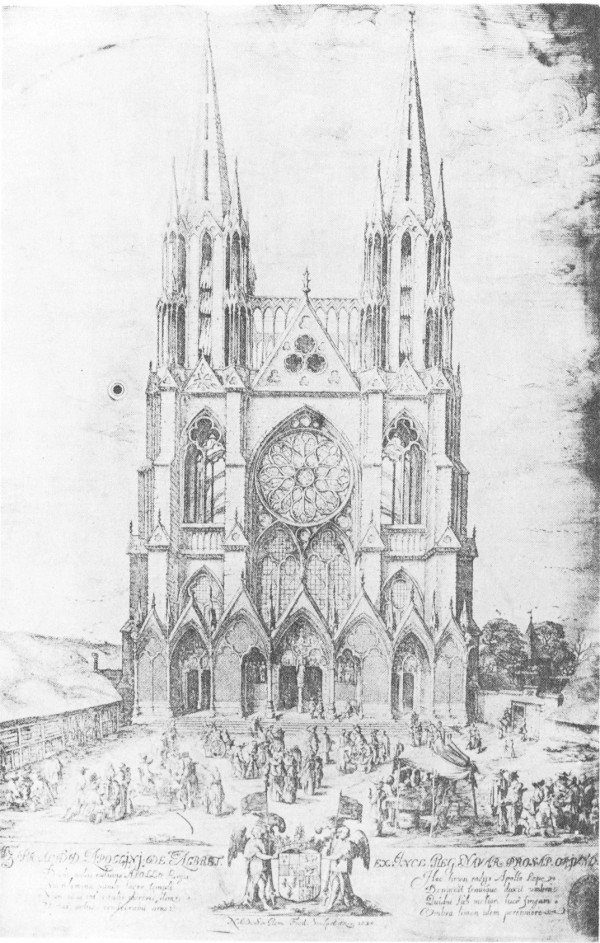

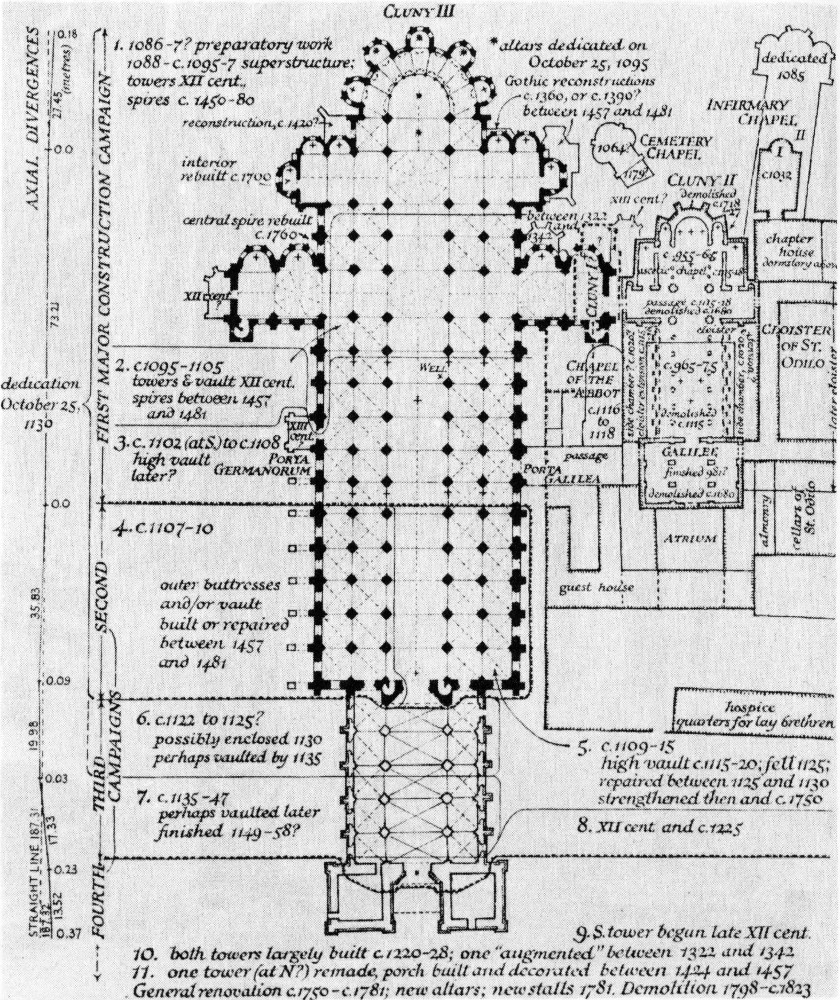

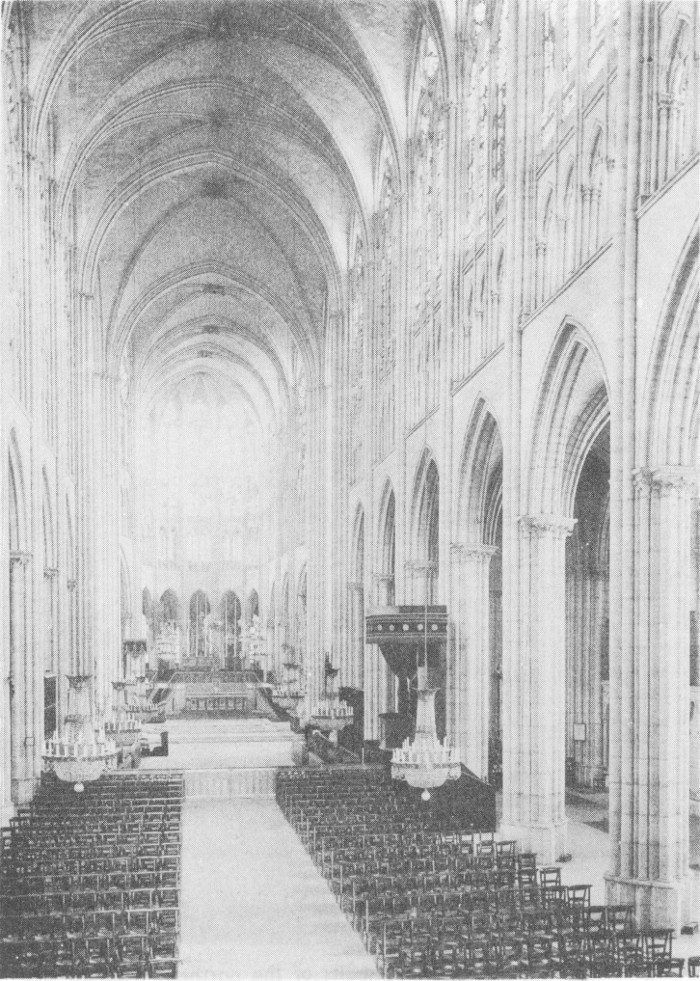

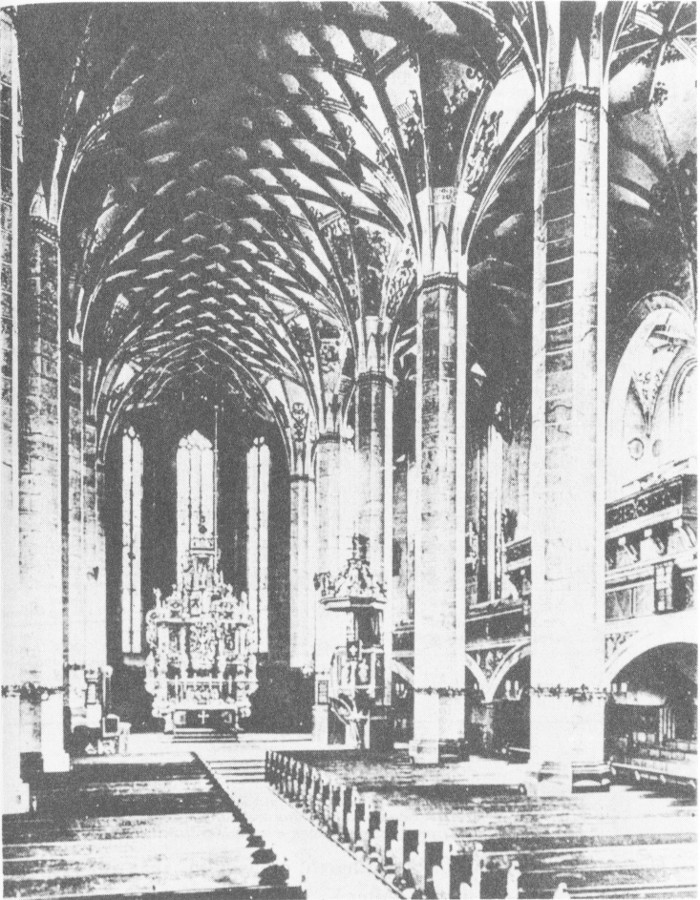

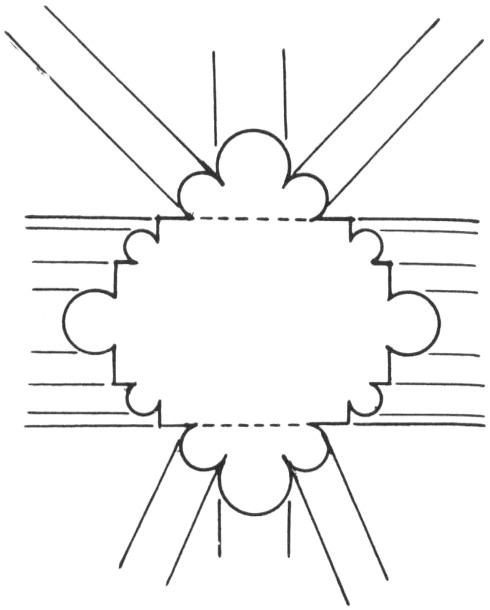

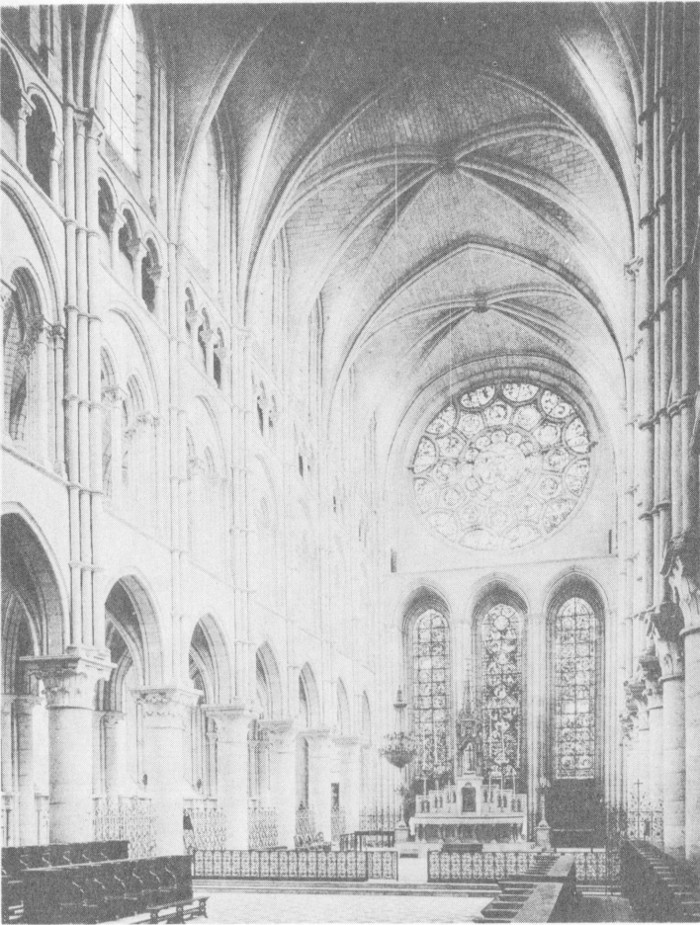

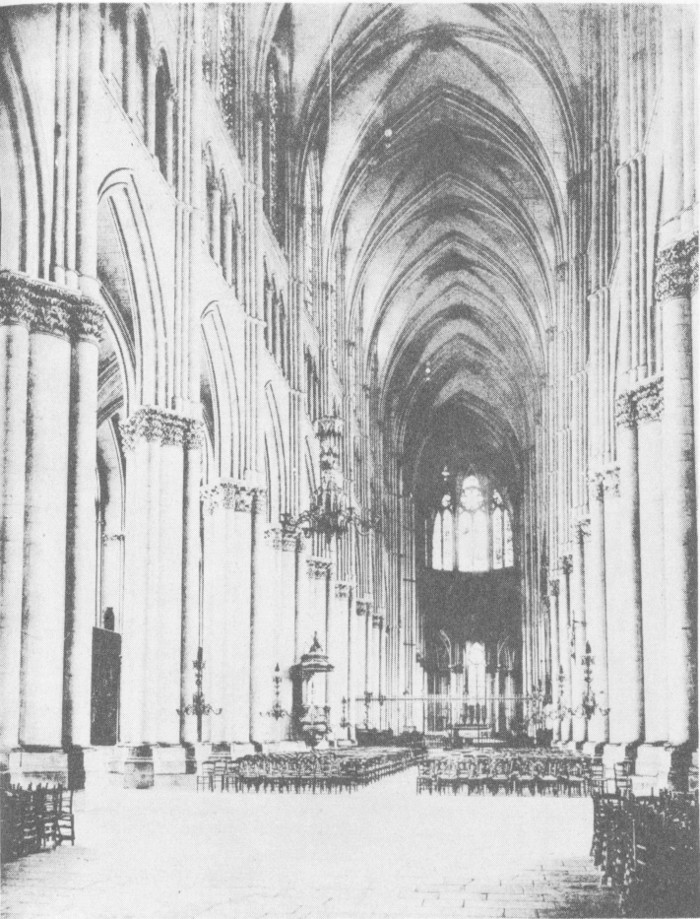

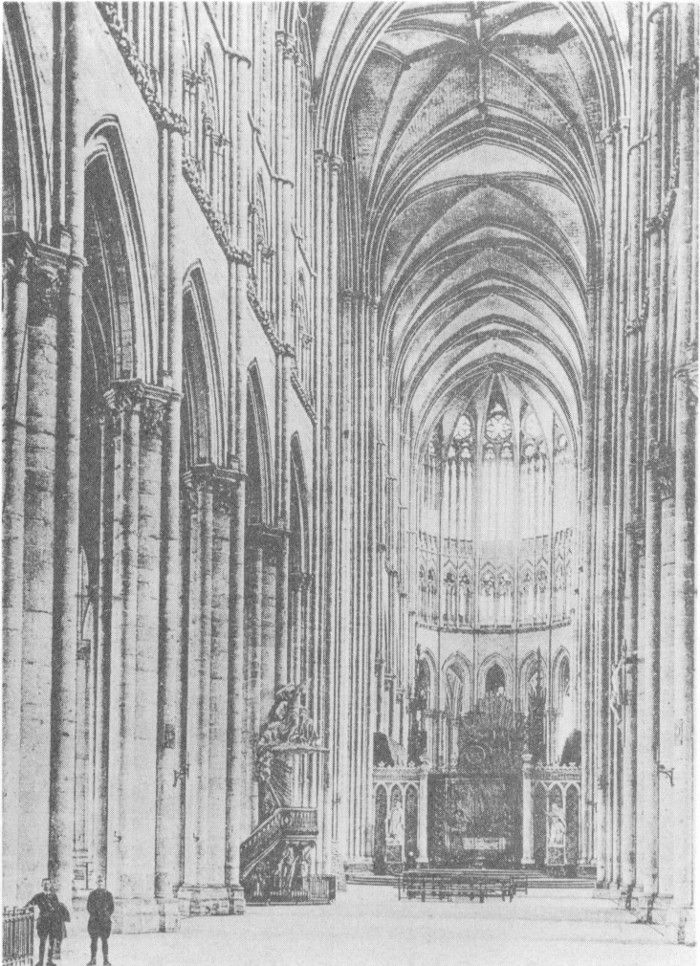

It was, however, in architecture that the habit of clarification achieved its greatest triumphs. As High Scholasticism was governed by the principle of manifestatio, so was High Gothic architecture dominated—as already observed by Suger—by what may be called the “principle of transparency.” Pre-Scholasticism had insulated faith from reason by an impervious barrier much as a Romanesque structure (fig. 8) conveys the impression of a space determinate and impenetrable, whether we find ourselves inside or outside the edifice. Mysticism was to drown reason in faith, and nominalism was to completely disconnect one from the other; and both these attitudes may be said to find expression in the Late Gothic hall church. Its barnlike shell encloses an often wildly pictorial and always apparently boundless interior (fig. 9) and thus creates a space determinate and impenetrable from without but indeterminate and penetrable from within. High Scholastic philosophy, however, severely limited the sanctuary of faith from the sphere of rational knowledge yet insisted that the content of this sanctuary remain clearly discernible. And so did High Gothic architecture delimit interior volume from exterior space yet insist that it project itself, as it were, through the encompassing structure (fig. 15 and 16); so that, for example, the cross section of the nave can be read off from the façade (fig. 34).

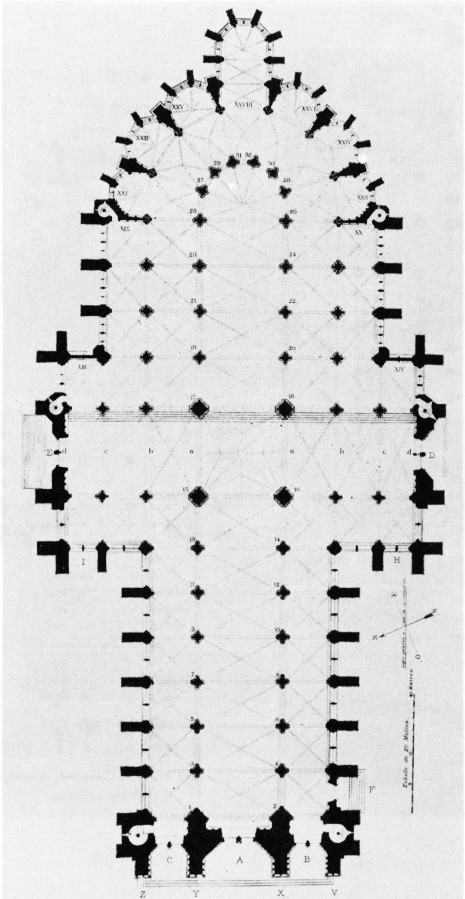

Like the High Scholastic Summa, the High Gothic cathedral aimed, first of all, at “totality” and therefore tended to approximate, by synthesis as well as elimination, one perfect and final solution; we may therefore speak of the High Gothic plan or the High Gothic system with much more confidence than would be possible in any other period. In its imagery, the High Gothic cathedral sought to embody the whole of Christian knowledge, theological, moral, natural, and historical, with everything in its place and that which no longer found its place, suppressed. In structural design, it similarly sought to synthesize all major motifs handed down by separate channels and finally achieved an unparalleled balance between the basilica and the central plan type, suppressing all elements that might endanger this balance, such as the crypt, the galleries, and towers other than the two in front.

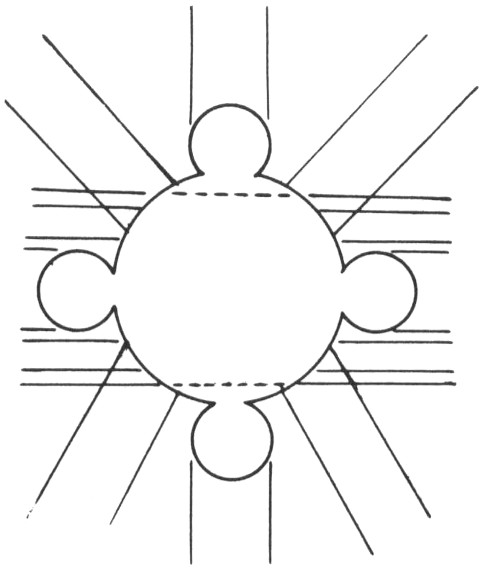

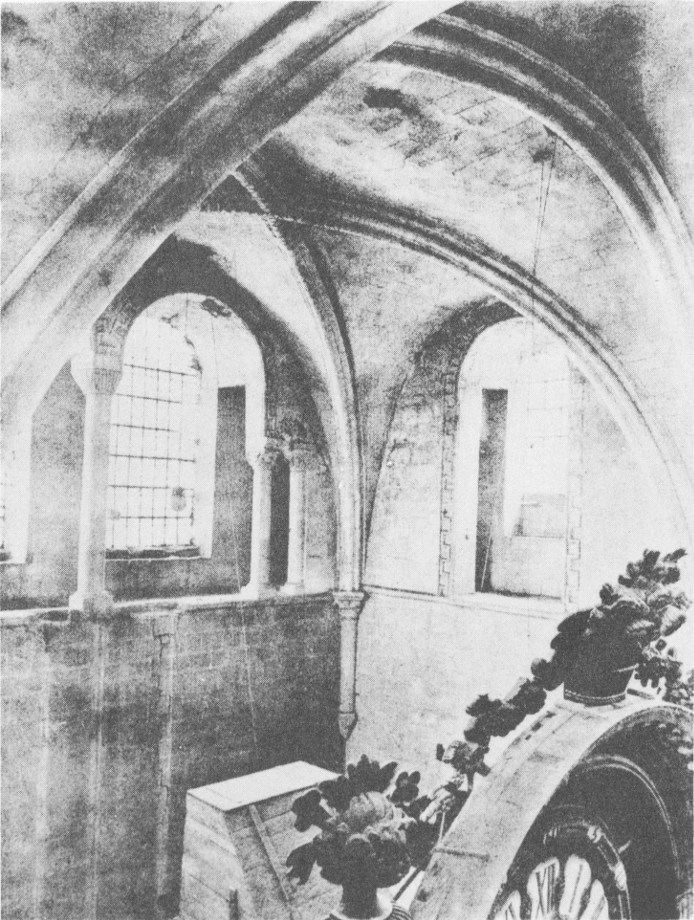

The second requirement of Scholastic writing, “arrangement according to a system of homologous parts and parts of parts,” is most graphically expressed in the uniform division and subdivision of the whole structure. Instead of the Romanesque variety of western and eastern vaulting forms, often appearing in one and the same building (groin vaults, rib vaults, barrels, domes, and half-domes), we have the newly developed rib vault exclusively so that the vaults of even the apse, the chapels and the ambulatory no longer differ in kind from those of the nave and transept (fig. 10 and 11). Since Amiens, rounded surfaces were entirely eliminated, except, of course, for the webbing of the vaults. Instead of the contrast that normally existed between tripartite naves and undivided transepts (or quinquepartite naves and tripartite transepts) we have tripartition in both cases; and instead of the disparity (either in size, or in the type of covering, or in both) between the bays of the high nave and those of the side aisles, we have the “uniform travée,” in which one rib-vaulted central bay connects with one rib-vaulted aisle bay on either side. The whole is thus composed of smallest units—one might almost speak of articuli—which are homologous in that they are all triangular in groundplan and in that each of these triangles shares its sides with its neighbors.

|  |  |

As a result of this homology we perceive what corresponds to the hierarchy of “logical levels” in a well-organized Scholastic treatise. Dividing the entire structure, as was customary in the period itself, into three main parts, the nave, the transept, and the chevet (which in turn comprises the fore-choir and the choir proper), and distinguishing, within these parts, between high nave and side-aisles, on the one hand, and between apse, ambulatory, and hemicycle of chapels, on the other, we can observe analogous relations to obtain: first, between each central bay, the whole of the central nave, and the entire nave, transept or fore-choir, respectively; second, between each side aisle bay, the whole of each side aisle, and the entire nave, transept or fore-choir, respectively; third, between each sector of the apse, the whole apse, and the entire choir; fourth, between each section of the ambulatory, the whole ambulatory and the entire choir; and fifth, between each chapel, the whole hemicycle of chapels, and the entire choir.

It is not possible here—nor is it necessary—to describe how this principle of progressive divisibility (or, to look at it the other way, multiplicability) increasingly affected the entire edifice down to the smallest detail. At the height of the development, supports were divided and subdivided into main piers, major shafts, minor shafts, and still minor shafts; the tracery of windows, triforia, and blind arcades into primary, secondary, and tertiary mullions and profiles; ribs and arches into a series of moldings (fig. 22). It may be mentioned, however, that the very principle of homology that controls the whole process implies and accounts for the relative uniformity which distinguishes the High Gothic vocabulary from the Romanesque. All parts that are on the same “logical level”—and this is especially noticeable in those decorative and representational features which, in architecture, correspond to Thomas Aquinas’s similitudines— came to be conceived of as members of one class, so that the enormous variety in, for instance, the shape of canopies, the decoration of socles and archevaults, and, above all, the form of piers and capitals tended to be suppressed in favor of standard types admitting only of such variations as would occur in nature among individuals of one species. Even in the world of fashion the thirteenth century is distinguished by a reasonableness and uniformity (even as far as the difference between masculine and feminine costumes is concerned) which was equally foreign to the preceding and to the following period.

The theoretically illimited fractionization of the edifice is limited by what corresponds to the third requirement of Scholastic writing: “distinctness and deductive cogency.” According to classic High Gothic standards the individual elements, while forming an indiscerptible whole, yet must proclaim their identity by remaining clearly separated from each other—the shafts from the wall or the core of the pier, the ribs from their neighbors, all vertical members from their arches; and there must be an unequivocal correlation between them. We must be able to tell which element belongs to which, from which results what might be called a “postulate of mutual inferability”—not in dimensions, as in classical architecture, but in conformation. While Late Gothic permitted, even delighted in, flowing transitions and interpenetrations, and loved to defy the rule of correlation by, for instance, over-membrification of the ceiling and under-membrification of the supports (fig. 9), the classic style demands that we be able to infer, not only the interior from the exterior or the shape of the side aisles from that of the central nave but also, say, the organization of the whole system from the cross section of one pier.

The last-named instance is especially instructive. In order to establish uniformity among all the supports, including those in the rond-point (and also, perhaps, in deference to a latent classicizing impulse), the builders of the most important structures after Senlis, Noyon, and Sens had abandoned the compound pier and had sprung the nave arcades from monocylindrical piers (fig. 18). Note 30 This, of course, made it impossible to “express,” as it were, the superstructure in the conformation of the supports. In order to accomplish this and yet preserve the now accepted form, there was invented the pilier cantonné, the columnar pier with four applied colonnettes (fig. 19-21). However, while this type, adopted in Chartres, Reims, and Amiens, Note 31 permitted the “expression” of the transverse ribs of the nave and side aisles as well as the longitudinal arches of the nave arcades, it did not permit the “expression” of the diagonals (fig. 51). The final solution was found (in St.-Denis) by the resumption of the compound pier, reorganized, however, in such a way that it “expressed” every feature of a High Gothic superstructure (fig. 22). The inner profile of the nave arches is taken up by a strong colonnette, their outer profile by a slighter one, the transverse and diagonal ribs of the nave by three tall shafts (the central one stronger than the two others) to which correspond three analogous colonnettes for the transverse and diagonal ribs of the side-aisles; and even what remains of the nave wall—the only element that stubbornly persisted in being “wall”—is “manifested” in the rectangular, still “mural” core of the pier itself (fig. 52). Note 32

|  |  |  |

This is indeed “rationalism.” It is not quite the rationalism conceived by Choisy and Viollet-le-Duc, Note 33 for the compound piers of St.-Denis have no functional, let alone economic, advantages over the piliers cantonnés of Reims or Amiens; but neither is it—as Pol Abraham would have us believe—“illusionism.” Note 34 From the point of view of the modern archaeologist this famous quarrel between Pol Abraham and the functionalists can be settled by the reasonable compromise proposed by Marcel Aubert and Henri Focillon and, as a matter of fact, already envisaged by Ernst Gall. Note 35

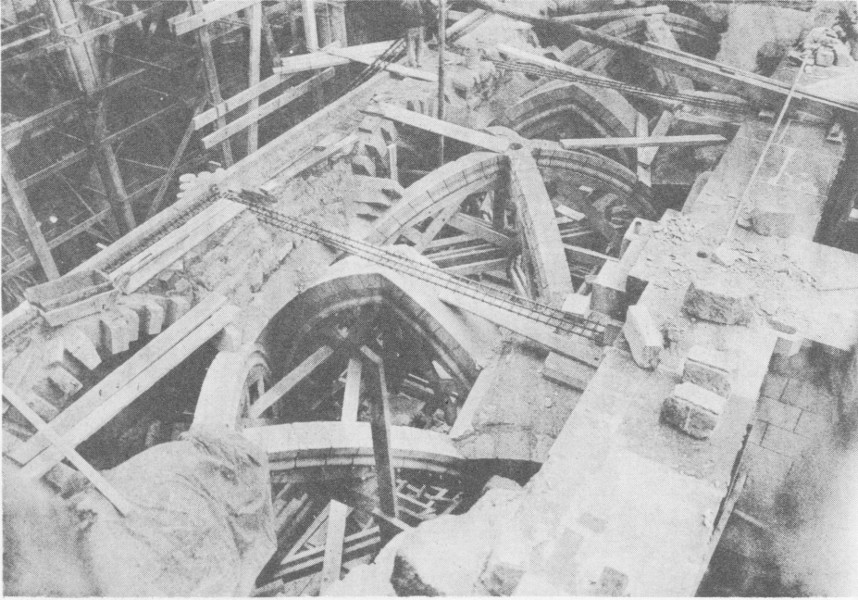

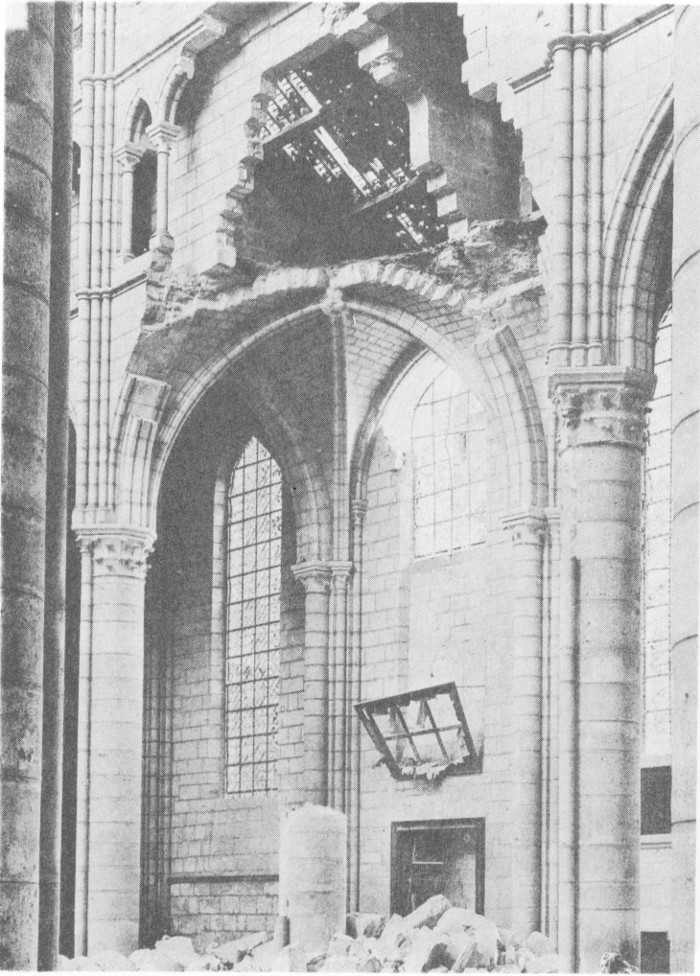

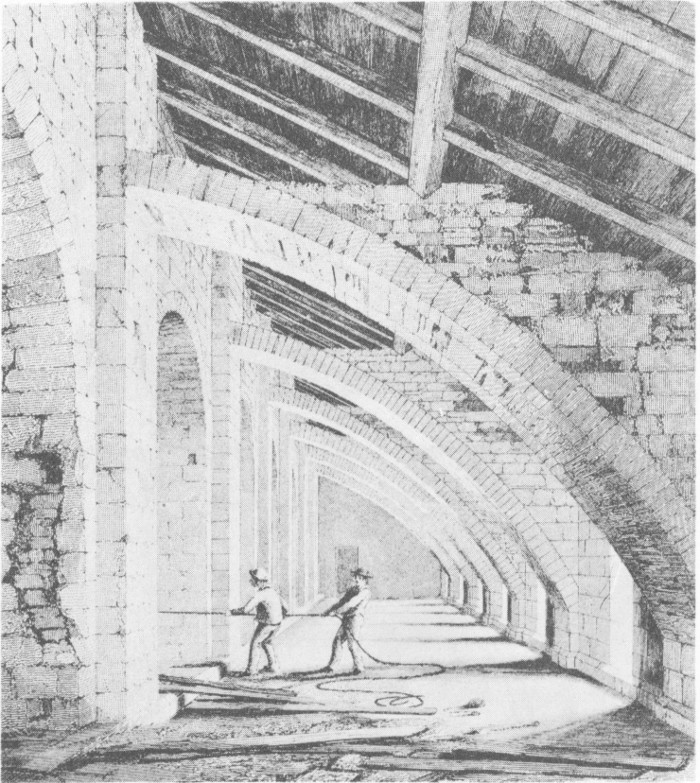

No doubt Pol Abraham is wrong in denying the practical value of even such features as ribs and flying buttresses. The skeleton of “independently constructed ribs” (arcus singulariter voluti), Note 36 much heavier and more robust than their graceful profiles lead us to believe (fig. 24), did have considerable technical advantages in that it made it possible to vault the webs in freehand (which saved much wood and labor for centering) and to reduce their thickness; for according to complicated modern calculations, the simple result of which was so well known, empirically, to the Gothic builders that they took it for granted in their writings, Note 37 an arch twice as thick as another is, ceteris paribus, just twice as strong; which means that ribs do reinforce the vault. That Gothic vaults have been known to survive when the ribs were blasted away by artillery fire in World War I does not prove that they would have survived had they been deprived of their ribs after seven weeks instead of after seven centuries; for ancient masonry will hold together by sheer cohesion so that major portions even of the walls may be seen hanging, as it were, in position after the loss of their supports (fig. 25). Note 38 Buttresses and flying buttresses do counteract the deformative forces which threaten the stability of every vault. Note 39 And that the Gothic masters—excepting only those headstrong Milanese ignoramuses who blandly contended that “no thrust upon the buttresses is exerted by vaults with pointed arches”—were fully aware of this is documented by several texts and attested to by their very trade expressions such as contrefort, bouterec (hence our “buttress”), arc-boutant, or the German strebe (hence, interestingly enough, the Spanish estribo), all of which denote the function of a thrust or counterthrust. Note 40 The upper range of flying buttresses— subsequently added in Chartres but planned from the outset in Reims and in most major edifices after that—may well have been intended to lend support to the steeper, heavier roofs and, possibly, to resist the wind pressure against them. Note 41 Even tracery has a certain practical value in that it facilitates the installation and aids the preservation of glass.

|  |  |

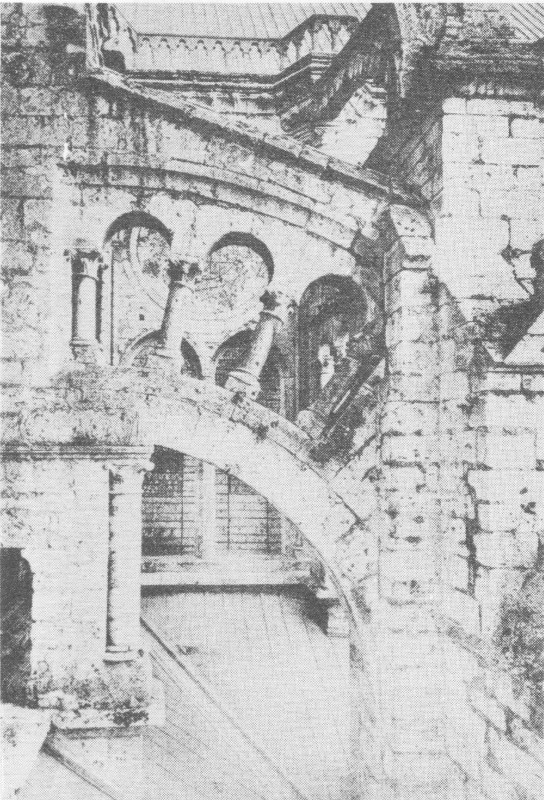

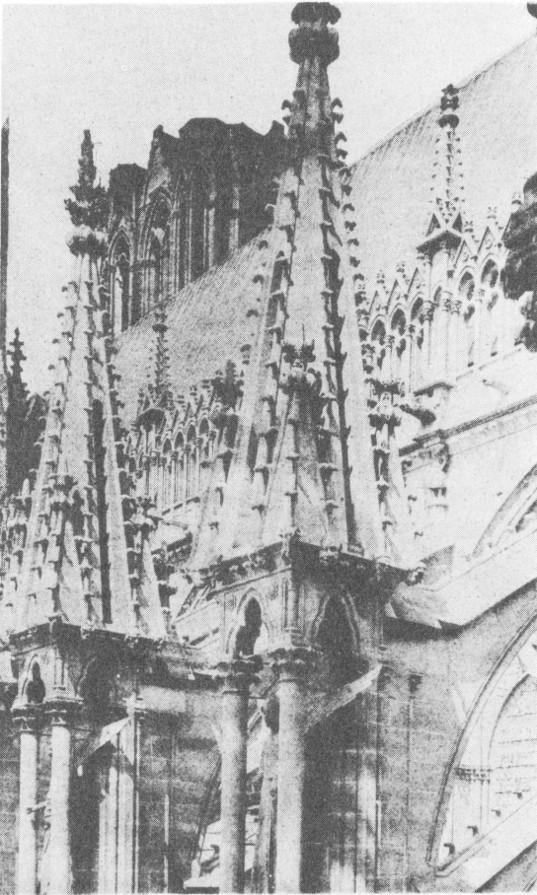

On the other hand, it is equally true that the earliest genuine ribs appear in connection with heavy groin vaults, where they could not have been constructed “independently” and thus would neither have saved centering nor would have had much statical value afterwards (fig. 23); Note 42 it is also true that the flying buttresses of Chartres, their functional importance notwithstanding, appealed to the aesthetic sense so much so that the master of the beautiful Madonna in the north transept of Reims Cathedral repeated them, en miniature, in the Madonna’s aedicule (fig. 26 and 27). The admirable architect of St.-Ouen in Rouen, whose design most closely approximates the modern standards of statical efficiency, Note 43 managed without an upper range of flying buttresses. And on no account could there have been any practical reason for that elaboration of the buttressing system which transforms it into a filigree of colonnettes, tabernacles, pinnacles, and tracery (fig. 29). The largest of all stained glass windows, the west window of Chartres, has survived seven centuries without any tracery; and that the blind tracery applied to solid surfaces has no technical importance whatsoever goes without saying.

|  |  |  |

However, this whole discussion is not to the point. With reference to twelfth and thirteenth century architecture, the alternative, “all is function—all is illusion,” is as little valid as would be, with reference to twelfth and thirteenth century philosophy, the alternative “all is search for truth—all is intellectual gymnastics and oratory.” The ribs of Caen and Durham, not as yet singulariter voluti, began by saying something before being able to do it. The flying buttresses of Caen and Durham, still hidden beneath the roofs of the side aisles (fig. 28), began by doing something before being permitted to say so. Ultimately, the flying buttress learned to talk, the rib learned to work, and both learned to proclaim what they were doing in language more circumstantial, explicit, and ornate than was necessary for mere efficiency; and this applies also to the conformation of the piers and the tracery which had been talking as well as working all the time.

We are faced neither with “rationalism” in a purely functionalistic sense nor with “illusion” in the sense of modern l’art pour l’art aesthetics. We are faced with what may be termed a “visual logic” illustrative of Thomas Aquinas’s nam et sensus ratio quaedam est. A man imbued with the Scholastic habit would look upon the mode of architectural presentation, just as he looked upon the mode of literary presentation, from the point of view of manifestatio. He would have taken it for granted that the primary purpose of the many elements that compose a cathedral was to ensure stability, just as he took it for granted that the primary purpose of the many elements that constitute a Summa was to ensure validity.

But he would not have been satisfied had not the membrification of the edifice permitted him to re-experience the very processes of architectural composition just as the membrification of the Summa permitted him to re-experience the very processes of cogitation. To him, the panoply of shafts, ribs, buttresses, tracery, pinnacles, and crockets was a self-analysis and self-explication of architecture much as the customary apparatus of parts, distinctions, questions, and articles was, to him, a self-analysis and self-explication of reason. Where the humanistic mind demanded a maximum of “harmony” (impeccable diction in writing, impeccable proportion, so sorely missed in Gothic structures by Vasari, Note 44 in architecture), the Scholastic mind demanded a maximum of explicitness. It accepted and insisted upon a gratuitous clarification of function through form just as it accepted and insisted upon a gratuitous clarification of thought through language.