II

During the “concentrated” phase of this astonishingly synchronous development, viz., in the period between about 1130-40 and about 1270, we can observe, it seems to me, a connection between Gothic art and Scholasticism which is more concrete than a mere “parallelism” and yet more general than those individual (and very important) “influences” which are inevitably exerted on painters, sculptors, or architects by erudite advisers. In contrast to a mere parallelism, the connection which I have in mind is a genuine cause-and- effect relation; but in contrast to an individual influence, this cause-and-effect relation comes about by diffusion rather than by direct impact. It comes about by the spreading of what may be called, for want of a better term, a mental habit—reducing this overworked cliché to its precise Scholastic sense as a “principle that regulates the act,” principium importans ordinem ad actum.Note 7 Such mental habits are at work in all and every civilization. All modern writing on history is permeated by the idea of evolution (an idea the evolution of which needs much more study than it has received thus far and seems to enter a critical phase right now); and all of us, without a thorough knowledge of biochemistry or psychoanalysis, speak with the greatest of ease of vitamin deficiencies, allergies, mother fixations, and inferiority complexes.

Often it is difficult or impossible to single out one habit- forming force from many others and to imagine the channels of transmission. However, the period from about 1130-40 to about 1270 and the “100-mile zone around Paris” constitute an exception. In this tight little sphere Scholasticism possessed what amounted to a monopoly in education. By and large, intellectual training shifted from the monastic schools to institutions urban rather than rural, cosmopolitan rather than regional, and, so to speak, only half ecclesiastic: to the cathedral schools, the universities, and the studia of the new mendicant orders—nearly all of them products of the thirteenth century—whose members played an increasingly important role within the universities themselves. And as the Scholastic movement, prepared by Benedictine learning and initiated by Lanfranc and Anselm of Bec, was carried on and brought to fruition by the Dominicans and Franciscans, so did the Gothic style, prepared in Benedictine monasteries and initiated by Suger of St.-Denis, achieve its culmination in the great city churches. It is significant that during the Romanesque period the greatest names in architectural history are those of Benedictine abbeys, in the High Gothic period those of cathedrals, and in the Late Gothic periods those of parish churches.

It is not very probable that the builders of Gothic structures read Gilbert de la Porrée or Thomas Aquinas in the original. But they were exposed to the Scholastic point of view in innumerable other ways, quite apart from the fact that their own work automatically brought them into a working association with those who devised the liturgical and iconographic programs. They had gone to school; they listened to sermons; they could attend the public disputationes de quolibet which, dealing as they did with all imaginable questions of the day, had developed into social events not unlike our operas, concerts, or public lectures; Note 8 and they could come into profitable contact with the learned on many other occasions. The very fact that neither the natural sciences nor the humanities nor even mathematics had evolved their special esoteric methods and terminologies kept the whole of human knowledge within the range of the normal, non-specialized intellect; and—perhaps the most important point—the entire social system was rapidly changing toward an urban professionalism. Not as yet hardened into the later guild and “Bauhütten” systems, it provided a meeting ground where the priest and the layman, the poet and the lawyer, the scholar and the artisan could get together on terms of near-equality. There appeared the professional, town-dwelling publisher (stationarius, hence our “stationer”), who, more or less strictly supervised by a university, produced manuscript books en masse with the aid of hired scribes, together with the bookseller (mentioned from about 1170), the book-lender, the bookbinder, and the book-illuminator (by the end of the thirteenth century the enlumineurs already occupied a whole street in Paris); the professional, town-dwelling painter, sculptor, and jeweller; the professional, town-dwelling scholar who, though usually a cleric, yet devoted the substance of his life to writing and teaching (hence the words “scholastic” and “scholasticism”); and, last but not least, the professional, town-dwelling architect.

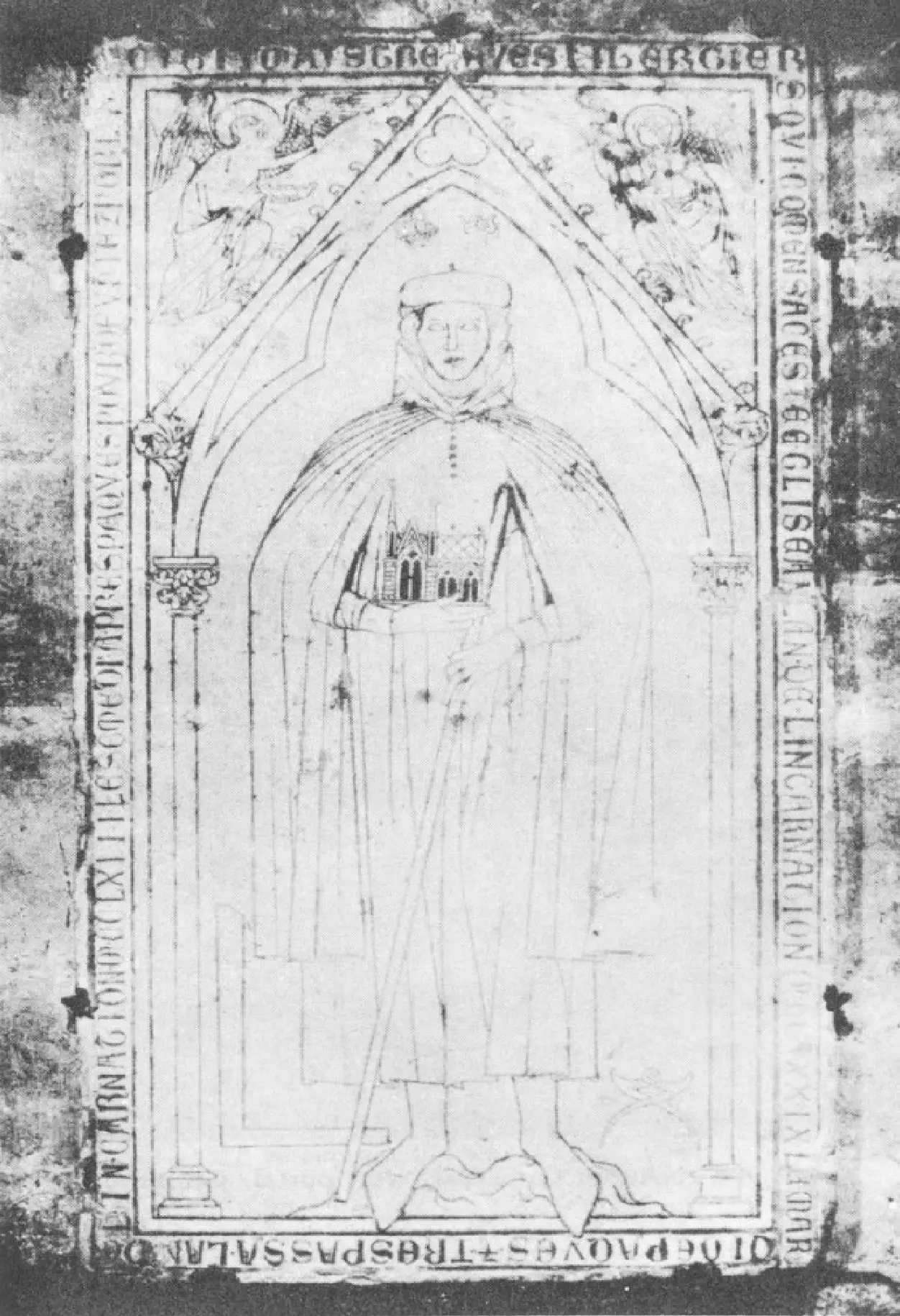

This professional architect—“professional” in contradistinction to the monastic equivalent of what in modern times is called the gentleman architect—would rise from the ranks and supervise the work in person. In doing so he grew into a man of the world, widely travelled, often well read, and enjoying a social prestige unequalled before and unsurpassed since. Freely selected propter sagacitatem ingenii, he drew a salary envied by the lower clergy and would appear at the site, “carrying gloves and a rod” (virga), to give those curt orders that became a byword in French literature whenever a writer wished to describe a man who does things well and with superior assurance: “Par cy me le taille.” Note 9 His portrait would figure together with that of the founding bishop in the “labyrinths” of the great cathedrals. After Hugues Libergier, the master of the lost St.- Nicaise in Reims, had died in 1263, he was accorded the unheard-of honor of being immortalized in an effigy that shows him not only clad in something like academic garb but also carrying a model of “his” church—a privilege previously accorded only to princely donors (fig. 1). And Pierre de Montereau—indeed the most logical architect who ever lived —is designated on his tombstone in St.-Germain-des-Prés as “Doctor Lathomorum”: by 1267, it seems, the architect himself had come to be looked upon as a kind of Scholastic.